Israeli artist charts human history through the flat screen

In a Netanya gallery, Adi Dulza has created a sophisticated sculpture-driven exhibition that presents the clichés of our time.

By Galia Yahav | Feb. 12, 2015 | 11:31 AM

By Galia Yahav | Feb. 12, 2015 | 11:31 AM

'Untitled', Adi Dulza, 2014

Empty television cartons take up the front space of the Al Ha Tzuk (Cliff) Gallery in Netanya, where Adi Dulza’s exhibition “In-Formation” is now showing (until March 1). The empty boxes form a colorful installation, titled “Sea of Tranquillity,” which has a still-life character, resembling a ridgeline or an urban skyline. They fill up most of the space, leaving the viewer room on the edges. The boxes close to the viewer lie separately on the floor, the more distant ones are stacked on one other, creating an expanding, ever-higher triangle. The packages look like buildings, like extras in a futuristic movie, the taller ones behind, their entire role being to observe the silence.

Like threatening gatekeepers, Fuji Japan, Pilot, Samsung, Akai, Thomson, Skyworth close ranks and create a wall, returning a blank gaze. Rectangular elements straddling the width of the space, they are adorned with texts and photographs bearing a coded cultural meaning to be deciphered.

Empty television cartons take up the front space of the Al Ha Tzuk (Cliff) Gallery in Netanya, where Adi Dulza’s exhibition “In-Formation” is now showing (until March 1). The empty boxes form a colorful installation, titled “Sea of Tranquillity,” which has a still-life character, resembling a ridgeline or an urban skyline. They fill up most of the space, leaving the viewer room on the edges. The boxes close to the viewer lie separately on the floor, the more distant ones are stacked on one other, creating an expanding, ever-higher triangle. The packages look like buildings, like extras in a futuristic movie, the taller ones behind, their entire role being to observe the silence.

Like threatening gatekeepers, Fuji Japan, Pilot, Samsung, Akai, Thomson, Skyworth close ranks and create a wall, returning a blank gaze. Rectangular elements straddling the width of the space, they are adorned with texts and photographs bearing a coded cultural meaning to be deciphered.

'Sea of tranquility', Adi Dulza, 2014

The curator, Maya Kashevitz, writes that the empty boxes represent the horizon toward which progress looks. The different sizes, she observes, illustrate the linear transformation that technology, and with it humanity, undergoes, toward that which is bigger, faster, multidimensional, smart; the consumerist hyper-obsession with a relentless ambition to upgrade. In addition, the boxes represent sculpture made of junk and scraps, in the tradition of kindergarten-type constructivism, in which empty packages collected by parents are fastened together with glue – an optimistic family-collage approach in which any two objects stuck together produce a new creation.

In any event, the cumulative effect is of a multiplicity of screens, as in the work of the video artist Nam June Paik. But in contrast to Paik’s use of actual televisions as sculpture or as a space-blocking design element, Dulza no longer has recourse to the content of the broadcasts or to the object itself. He makes do with the seemingly sparse, but in practice bulimic, information that appears on the hollow cartons. The information signifies for us the transition from a holistic worldview of a globe to a global worldview of a flat screen.

New Age relaxation

Now, with the world having reverted to flatness, the installation at moments resembles church decorations that explain to visitors the history of humanity, the formative myths, the criteria of morality. A giant eye drawn in blue on one box betrays the Cyclops that looks at us in every home and in every situation. Here’s a child sitting on the grass and laughing merrily, a pyramid that rises in a desert landscape; spectacular colored fish in water declare implicitly that televisions are aquariums. Here we have skyscrapers whose diamond lights are photographed “in reality” and again “on a screen” in order to persuade us that there is no difference, either in the resolution or in the user’s experience, between the representation and the reality.

The sound that accompanies this installation – that of waves – underlines the effect of mild hypnosis, New Age-style relaxation in which peace begins from within me and I am the star of The Truman Show. It’s an analogic wave for the domesticated tsunami of what the curator calls clichés that encourage consumerism.

The curator, Maya Kashevitz, writes that the empty boxes represent the horizon toward which progress looks. The different sizes, she observes, illustrate the linear transformation that technology, and with it humanity, undergoes, toward that which is bigger, faster, multidimensional, smart; the consumerist hyper-obsession with a relentless ambition to upgrade. In addition, the boxes represent sculpture made of junk and scraps, in the tradition of kindergarten-type constructivism, in which empty packages collected by parents are fastened together with glue – an optimistic family-collage approach in which any two objects stuck together produce a new creation.

In any event, the cumulative effect is of a multiplicity of screens, as in the work of the video artist Nam June Paik. But in contrast to Paik’s use of actual televisions as sculpture or as a space-blocking design element, Dulza no longer has recourse to the content of the broadcasts or to the object itself. He makes do with the seemingly sparse, but in practice bulimic, information that appears on the hollow cartons. The information signifies for us the transition from a holistic worldview of a globe to a global worldview of a flat screen.

New Age relaxation

Now, with the world having reverted to flatness, the installation at moments resembles church decorations that explain to visitors the history of humanity, the formative myths, the criteria of morality. A giant eye drawn in blue on one box betrays the Cyclops that looks at us in every home and in every situation. Here’s a child sitting on the grass and laughing merrily, a pyramid that rises in a desert landscape; spectacular colored fish in water declare implicitly that televisions are aquariums. Here we have skyscrapers whose diamond lights are photographed “in reality” and again “on a screen” in order to persuade us that there is no difference, either in the resolution or in the user’s experience, between the representation and the reality.

The sound that accompanies this installation – that of waves – underlines the effect of mild hypnosis, New Age-style relaxation in which peace begins from within me and I am the star of The Truman Show. It’s an analogic wave for the domesticated tsunami of what the curator calls clichés that encourage consumerism.

'Untitled', Adi Dulza, 2014

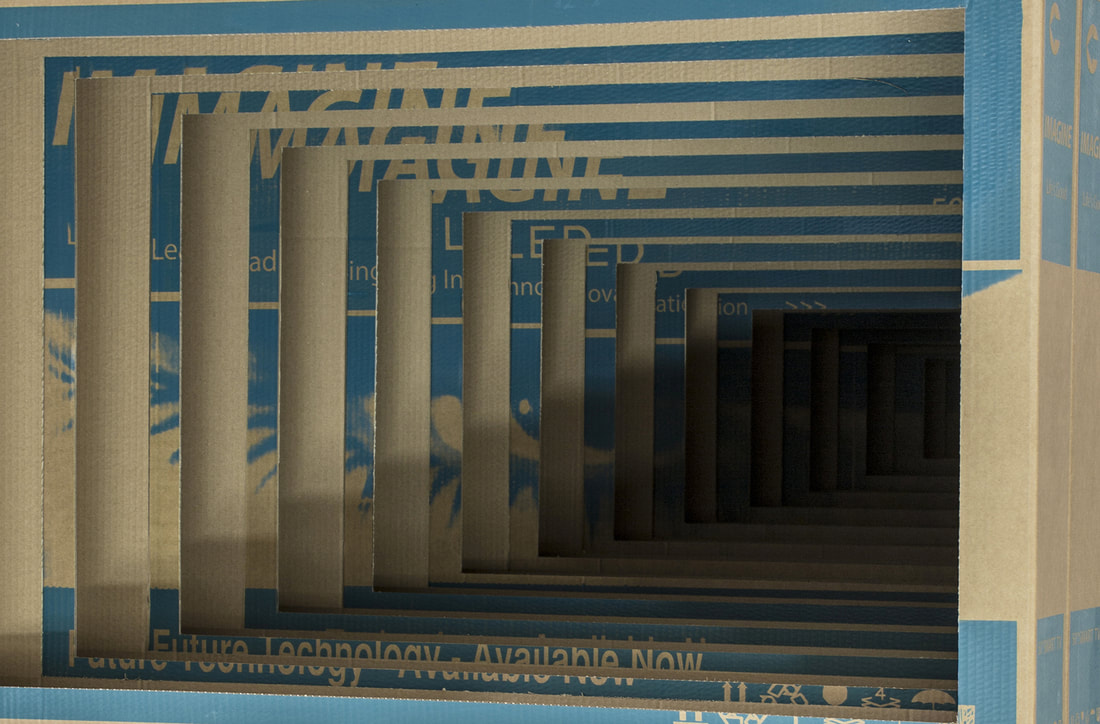

Two works in the rear space combine sculpture with video. On one side is a sculpture – a telescopic cardboard construction – of a fictitious company, “Imagine – Good Life.” The boxes are cut so they become progressively smaller, moving toward a vanishing point where there is a moving image: an excerpt from a video documentation of the phone call between U.S. President Richard Nixon and the Apollo 11 astronauts who landed on the moon, in which Nixon thanks them on behalf of the United States and on behalf of humanity. We see a diminished, distant fragment of the documentation, only mouth and receiver, the most salient image of communications in the 20th century.

The work recalls Nam June Paik’s “TV Buddha” (1974), in which a statue of Buddha views a television screen that acts as a mirror reflecting the viewer. That work is considered the salient harbinger of the era of narcissistic media, with its simultaneity of recording and dissemination and the mirror-like immediacy of the process of reflection. Its importance also lay in the encounter that was forged between Eastern art and Western technology.

But whereas Paik was a prophet of future technology, the dialogue that is planted within Dulza’s telescopic installation alludes to the rapid dating of the methods and the good intentions. “Hello Neil and Buzz,” Nixon says to Armstrong and Aldrin, who are at the Sea of Tranquility base on the moon – the source of Dulza’s title for the work. “I’m talking to you by telephone from the Oval Room at the White House,” the president continues, adding, “this has to be the most historic telephone call ever made.” Thanks to the astronauts, he continues, “the heavens have become a part of our world, and as you talk to us from the Sea of Tranquility it inspires us to redouble our efforts to bring peace and tranquility to Earth.” Nixon was not known as a peacemaker, but the nostalgic segment from the documentation of this moving moment brings to the fore the exhibition’s ambivalent thrust: the disappointing promise of the future, the hyper-reality and the Stone Age, the tremendous digital visions shattered on the crises of history, demonstrating their emptiness, like a LED box without the LED.

Sweet and sour

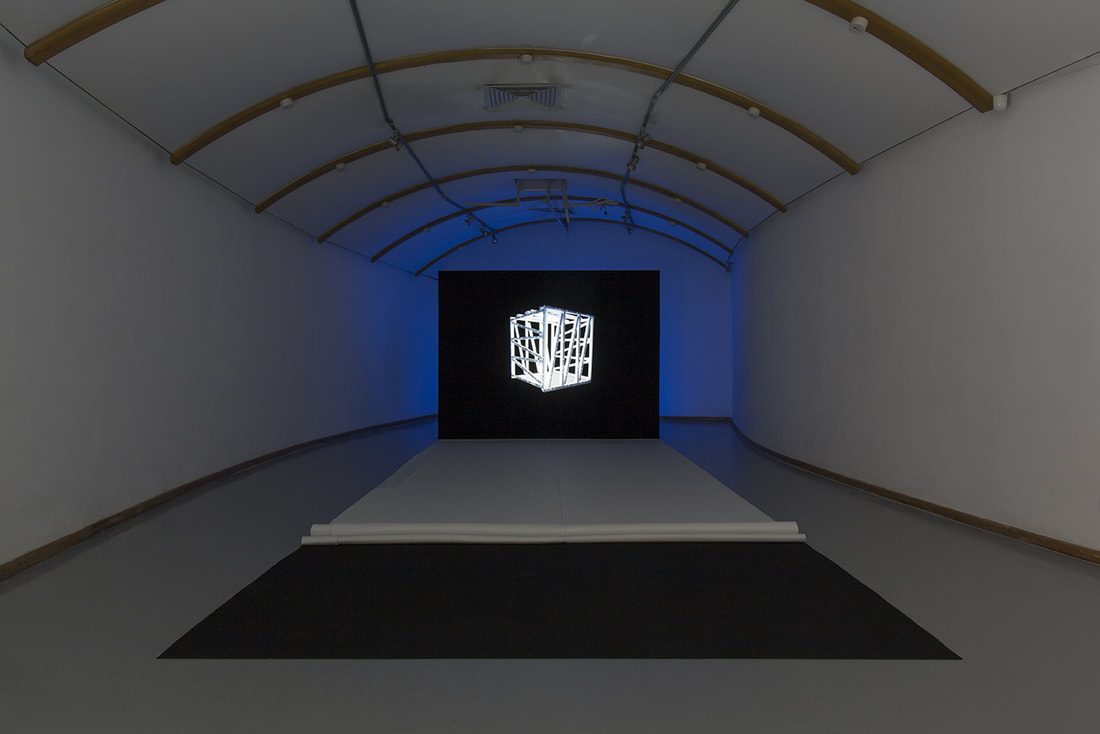

On the other side is a home movie screen on which a cube made of neon lighting appears. The cube glows against the black background like a logo fraught with promise, then flickers and is extinguished. The after-image remains burned into the screen, a metaphor for the way in which broadcast content remains burned into our consciousness for some time, like starlight that continues to wink at us even after the stars are already dead.

Two works in the rear space combine sculpture with video. On one side is a sculpture – a telescopic cardboard construction – of a fictitious company, “Imagine – Good Life.” The boxes are cut so they become progressively smaller, moving toward a vanishing point where there is a moving image: an excerpt from a video documentation of the phone call between U.S. President Richard Nixon and the Apollo 11 astronauts who landed on the moon, in which Nixon thanks them on behalf of the United States and on behalf of humanity. We see a diminished, distant fragment of the documentation, only mouth and receiver, the most salient image of communications in the 20th century.

The work recalls Nam June Paik’s “TV Buddha” (1974), in which a statue of Buddha views a television screen that acts as a mirror reflecting the viewer. That work is considered the salient harbinger of the era of narcissistic media, with its simultaneity of recording and dissemination and the mirror-like immediacy of the process of reflection. Its importance also lay in the encounter that was forged between Eastern art and Western technology.

But whereas Paik was a prophet of future technology, the dialogue that is planted within Dulza’s telescopic installation alludes to the rapid dating of the methods and the good intentions. “Hello Neil and Buzz,” Nixon says to Armstrong and Aldrin, who are at the Sea of Tranquility base on the moon – the source of Dulza’s title for the work. “I’m talking to you by telephone from the Oval Room at the White House,” the president continues, adding, “this has to be the most historic telephone call ever made.” Thanks to the astronauts, he continues, “the heavens have become a part of our world, and as you talk to us from the Sea of Tranquility it inspires us to redouble our efforts to bring peace and tranquility to Earth.” Nixon was not known as a peacemaker, but the nostalgic segment from the documentation of this moving moment brings to the fore the exhibition’s ambivalent thrust: the disappointing promise of the future, the hyper-reality and the Stone Age, the tremendous digital visions shattered on the crises of history, demonstrating their emptiness, like a LED box without the LED.

Sweet and sour

On the other side is a home movie screen on which a cube made of neon lighting appears. The cube glows against the black background like a logo fraught with promise, then flickers and is extinguished. The after-image remains burned into the screen, a metaphor for the way in which broadcast content remains burned into our consciousness for some time, like starlight that continues to wink at us even after the stars are already dead.

'Imagine', Adi Dulza, 2014

Another possibility arises from the ambivalent sweet-and-sour tone of the exhibition, one that is more than an indictment against the flattening of reality. The exhibition expresses not only great weariness at the accelerated pace of technology and at rampant consumerism; it also displays a certain yearning for an era in which technological enhancement was celebrated somewhat as an achievement, before becoming an archaeological find or old film footage.

The pleasure that arises from the exhibition is one which we’re familiar from ready-made products. It’s already imbued with sufficient intra-art history (beginning with cave walls) and plays with it like Lego bricks. Dulza’s attitude toward technology is not only one of protest, but also of adoption. He is offering an interesting sculptural option, according to which the most sophisticated monitor is an object that is cut off from its broadcast content; the information it conceals is no longer necessary and it has become a concrete design element in space, its world no longer necessary. Its shell is enough, marking it by its absence.

Another possibility arises from the ambivalent sweet-and-sour tone of the exhibition, one that is more than an indictment against the flattening of reality. The exhibition expresses not only great weariness at the accelerated pace of technology and at rampant consumerism; it also displays a certain yearning for an era in which technological enhancement was celebrated somewhat as an achievement, before becoming an archaeological find or old film footage.

The pleasure that arises from the exhibition is one which we’re familiar from ready-made products. It’s already imbued with sufficient intra-art history (beginning with cave walls) and plays with it like Lego bricks. Dulza’s attitude toward technology is not only one of protest, but also of adoption. He is offering an interesting sculptural option, according to which the most sophisticated monitor is an object that is cut off from its broadcast content; the information it conceals is no longer necessary and it has become a concrete design element in space, its world no longer necessary. Its shell is enough, marking it by its absence.

'Imagine', Adi Dulza, 2014