In-Formation

Al Ha-Tzuk Gallery, Netanya, 2014

Curator: Maya Kashevitz

Link to video: https://vimeo.com/122923886

Film: Nimrod Alexander Gershoni

Galia yahav in Haaretz Magazine: for English article

למאמר בעברית

Photos: Liron Sandman

Al Ha-Tzuk Gallery, Netanya, 2014

Curator: Maya Kashevitz

Link to video: https://vimeo.com/122923886

Film: Nimrod Alexander Gershoni

Galia yahav in Haaretz Magazine: for English article

למאמר בעברית

Photos: Liron Sandman

In-Formation

-----

-----

In a famous scene from Stanly Cubric's Clock Work Orange, Alex, the movie's sadistic protagonist, is sitting in a chair with his eyelids held open by a machine; In a "therapeutic" behaviouristic method made to help Alex change his bad ways, he is forced to watch the screen in front of him showing horrific videos of canonical representations of evil doing, while being fed drugs that induce nausea. Brainwashing through televised visual transmissions, with a positive goal in this case, peaks when the doctor conducting the experiment says to Alex "The choice was all yours".

In the exhibition "In-Formation", the television screen is a central visual motive. The artwork displayed offer a number of options accruing simultaneously and are ever changing. They have overlapping components and alongside them, there are struggles between content and form, nature and virtual space, (cynical) revelation and (conspiratorial) concealment, progress and consumerism, enslavement and freedom that confront the common logic with traps and paradoxes.

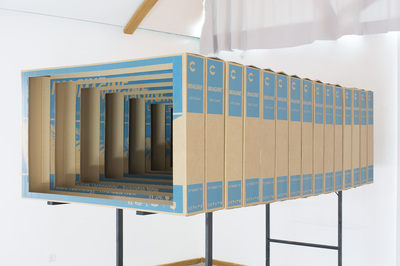

At the gallery's upper level stands a set of empty television screens boxes, loaded with imagery of nature and culture, a technological jungle of sorts where the viewer is invited to stroll. Artist Adi Dulza collected the boxes while wandering the city in a journey that became an obsession for collecting and creating a statistical database of purchases.

The exhibition's opening installation Sea Tranquility creates an informative flood of light, sound, imagery, structure and word. The empty boxes represent the horizon to which progress is striving for; boxes of black mirrors reflecting a portrait of humankind, of a plump and restless society. The different sizes emphasize the linear transformation of technology and humanity towards everything that is bigger, sharper, faster, economical, green, multi-dimensional, smart – the hyper-consumer's obsession with its constant need to upgrade.

Nature flickers out of imagery and slogan filled boxes with a sound simulating ocean waves. Wave in this case is also used in the context of information; the metaphorical choice in a smilingly natural noise, usually symbolizing calmness and tranquility, is an antithesis to the flood of information, the monsoon of transmission sent to the viewer through the dozens of illustrative imagery on the boxes - a domesticated wave of clichés encouraging consumer culture. Man's attempt to control nature, a nature that often threatens to destroy him, is shown in this installation through the use of a formalistic mass; an act of duplicating and replicating that tries to force constancy and structure on the chaos. Opposed to the control in the formalistic aspect, the artist's (and man's) attempt to control the distribution of messages is doomed to fail.

This failure brings to mind a claim by British scientist Richard Dawkins who coined the term "Meme" referring to the evolution of ideas and the way culture evolved through "theoretical viruses" transmitted from person to person - from language to religion and technology. Dawkins emphasizes the parasitical nature of Memes that do not exist to create a culture or for any other reason aside from their own survival. By doing so, the Memes turn the carriers – humans – into a passive, neutralized vessel, under a false impression of control.

In this work, Dulza treats the boxes as objects and representatives of visual Memes to create a sculptural environment – taking from the pioneer American artist Nam Jun Pike's use of television screens as an element and not an information transmit platform. Dulza neutralizes the technology that was used by Pike to create electronic manipulation on screens thus presents the viewer with empty wraps who become the medium itself.

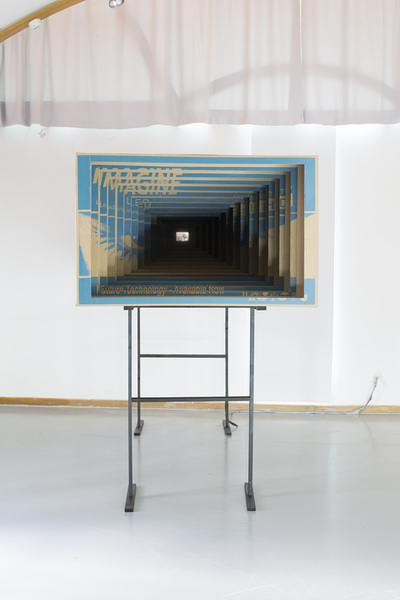

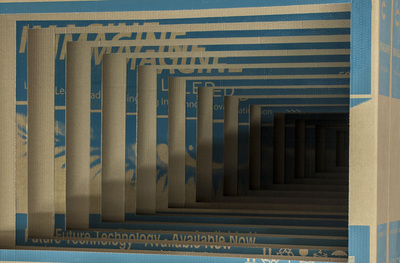

Going down the gallery stairs, the viewer is lead into the lower space and to the bottom of things. While the upper floor of the gallery is a kind of entrance hall or an overview, the second part of the exhibition reveals the process of content deconstructs into symbols, creating concept systems of power and control; at the right side, another pile of television boxes that the artist designed, printed and assembled. The eclectic street collection becomes an accumulation of the fictive "Imagine" company, brought together to create a telescopic construct with a moving image at its end. In a second glance, one can notice the iconic false-laced eye belonging to Clockwork Orange's star. The image breaks throughout the installation; it leads the viewer to its edge where a footage of the conversation between Richard Nixon and the Apolo 11 astronauts landing on the moon is revealed. Dulza uses what he sees as a founding and generic moment in the use of television for political means under pretense of heroism, the creation of a myth. The viewing is made possible through the "telescope" aimed to the video analogous to moon – distant by time and space and reduced in size into a fragment. The viewer's gaze is focused on Nixon's lips movement as if he is speaking directly to him, converting him into a believer. The loop or bug in the video surfaces a hidden paradox.

The installation refers to television as a powerful tool, static and firm, that contributes to what media researcher Marshall Mcluhan called "The Global Village". Just like the primitive tribe culture that transferred ideas and language with direct copying by word of mouth, the technological era changes the collective consciousness using the computer and the web. Language as a sign becomes more and more concentrated and symbolic (keyboard slang, emoticons, "Yo" application) contributing and strengthening the bandwagon effect. The information transferred through television is different than the one transferred through the internet: it is a tsunami of information that lets a person know what his wishes and needs are, what he should be afraid of, what he should believe in and how he should act. The television lets him know about the danger lurking around the corner and provides tools for solution; those will also deepen and root his dependence and subjugation to the system.

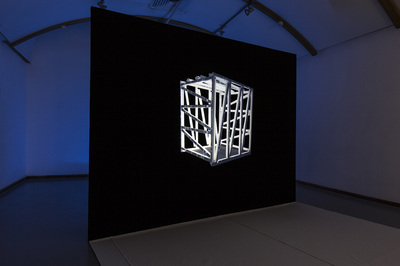

The same loop of consciousness continues in the last installation as well, it uses geometric language that provides an infrastructure for a discussion about collective and subjective mind. An image of a cube made out of neon lights flickers on a black home theatre screen; the image disappears after a short flash and a constant shape is left scorched on the screen. The "finite" keeps repeating, as a kind of prison for a thought that cannot look outside of itself or reflect from the outside. The light changes the power balance; it becomes the message instead of the "tool" that transfers it.

Technology shortens time and space. Physical products and ideas alike offer solutions and shortcuts to a faster, more convenient world but also estranged from the authentic experience of the natural. Technology cannot tolerate the other, thus it flattens reality and creates alienation between the subject and the role it must play as part of a collective that has imaginary myths and narratives. The exhibition refers to the changes and growth in knowledge consumption, the question of free choice and the role of the media in the process of consciousness change. It surfaces questions dealing with the triumph of technology over mind, a condition in which the subject is left passive when confronted with innovation that has crossed the perceptual speed of sound. The subject is being controlled in a concealed way – and remains a slave believing he is free.

Maya Kashevitz

*Translated from Hebrew by Gil Cohen

In the exhibition "In-Formation", the television screen is a central visual motive. The artwork displayed offer a number of options accruing simultaneously and are ever changing. They have overlapping components and alongside them, there are struggles between content and form, nature and virtual space, (cynical) revelation and (conspiratorial) concealment, progress and consumerism, enslavement and freedom that confront the common logic with traps and paradoxes.

At the gallery's upper level stands a set of empty television screens boxes, loaded with imagery of nature and culture, a technological jungle of sorts where the viewer is invited to stroll. Artist Adi Dulza collected the boxes while wandering the city in a journey that became an obsession for collecting and creating a statistical database of purchases.

The exhibition's opening installation Sea Tranquility creates an informative flood of light, sound, imagery, structure and word. The empty boxes represent the horizon to which progress is striving for; boxes of black mirrors reflecting a portrait of humankind, of a plump and restless society. The different sizes emphasize the linear transformation of technology and humanity towards everything that is bigger, sharper, faster, economical, green, multi-dimensional, smart – the hyper-consumer's obsession with its constant need to upgrade.

Nature flickers out of imagery and slogan filled boxes with a sound simulating ocean waves. Wave in this case is also used in the context of information; the metaphorical choice in a smilingly natural noise, usually symbolizing calmness and tranquility, is an antithesis to the flood of information, the monsoon of transmission sent to the viewer through the dozens of illustrative imagery on the boxes - a domesticated wave of clichés encouraging consumer culture. Man's attempt to control nature, a nature that often threatens to destroy him, is shown in this installation through the use of a formalistic mass; an act of duplicating and replicating that tries to force constancy and structure on the chaos. Opposed to the control in the formalistic aspect, the artist's (and man's) attempt to control the distribution of messages is doomed to fail.

This failure brings to mind a claim by British scientist Richard Dawkins who coined the term "Meme" referring to the evolution of ideas and the way culture evolved through "theoretical viruses" transmitted from person to person - from language to religion and technology. Dawkins emphasizes the parasitical nature of Memes that do not exist to create a culture or for any other reason aside from their own survival. By doing so, the Memes turn the carriers – humans – into a passive, neutralized vessel, under a false impression of control.

In this work, Dulza treats the boxes as objects and representatives of visual Memes to create a sculptural environment – taking from the pioneer American artist Nam Jun Pike's use of television screens as an element and not an information transmit platform. Dulza neutralizes the technology that was used by Pike to create electronic manipulation on screens thus presents the viewer with empty wraps who become the medium itself.

Going down the gallery stairs, the viewer is lead into the lower space and to the bottom of things. While the upper floor of the gallery is a kind of entrance hall or an overview, the second part of the exhibition reveals the process of content deconstructs into symbols, creating concept systems of power and control; at the right side, another pile of television boxes that the artist designed, printed and assembled. The eclectic street collection becomes an accumulation of the fictive "Imagine" company, brought together to create a telescopic construct with a moving image at its end. In a second glance, one can notice the iconic false-laced eye belonging to Clockwork Orange's star. The image breaks throughout the installation; it leads the viewer to its edge where a footage of the conversation between Richard Nixon and the Apolo 11 astronauts landing on the moon is revealed. Dulza uses what he sees as a founding and generic moment in the use of television for political means under pretense of heroism, the creation of a myth. The viewing is made possible through the "telescope" aimed to the video analogous to moon – distant by time and space and reduced in size into a fragment. The viewer's gaze is focused on Nixon's lips movement as if he is speaking directly to him, converting him into a believer. The loop or bug in the video surfaces a hidden paradox.

The installation refers to television as a powerful tool, static and firm, that contributes to what media researcher Marshall Mcluhan called "The Global Village". Just like the primitive tribe culture that transferred ideas and language with direct copying by word of mouth, the technological era changes the collective consciousness using the computer and the web. Language as a sign becomes more and more concentrated and symbolic (keyboard slang, emoticons, "Yo" application) contributing and strengthening the bandwagon effect. The information transferred through television is different than the one transferred through the internet: it is a tsunami of information that lets a person know what his wishes and needs are, what he should be afraid of, what he should believe in and how he should act. The television lets him know about the danger lurking around the corner and provides tools for solution; those will also deepen and root his dependence and subjugation to the system.

The same loop of consciousness continues in the last installation as well, it uses geometric language that provides an infrastructure for a discussion about collective and subjective mind. An image of a cube made out of neon lights flickers on a black home theatre screen; the image disappears after a short flash and a constant shape is left scorched on the screen. The "finite" keeps repeating, as a kind of prison for a thought that cannot look outside of itself or reflect from the outside. The light changes the power balance; it becomes the message instead of the "tool" that transfers it.

Technology shortens time and space. Physical products and ideas alike offer solutions and shortcuts to a faster, more convenient world but also estranged from the authentic experience of the natural. Technology cannot tolerate the other, thus it flattens reality and creates alienation between the subject and the role it must play as part of a collective that has imaginary myths and narratives. The exhibition refers to the changes and growth in knowledge consumption, the question of free choice and the role of the media in the process of consciousness change. It surfaces questions dealing with the triumph of technology over mind, a condition in which the subject is left passive when confronted with innovation that has crossed the perceptual speed of sound. The subject is being controlled in a concealed way – and remains a slave believing he is free.

Maya Kashevitz

*Translated from Hebrew by Gil Cohen

Copyright © 2015 Adi Dulza. All rights reserved